May 17, 2007 (LBO) - The theme of the 2007 World Telecom and Information Society Day (May 17

th) is connecting the young. It is difficult to connect the young without also connecting the old.

The young usually connect within the context of economic and other decisions made by family units.

This column examines what is required to connect families at the Bottom of the Pyramid (BOP) in Sri Lanka, drawing from the findings of a five-country Teleuse@BOP study.

Lessons learned

Post-apartheid South Africa pioneered the extension of telecom and Internet services to those lacking the wherewithal to own their own telephones, computers and Internet connections.

At the end of the 1990s, this social experiment had shown results. The low-cost, for-profit teleshops (USD 3,333 per teleshop with 5-10 telephone lines) were successful. The high-cost, not-for-profit telecenters (over USD 30,000 per telecenter with four computers and four telecom lines) had failed.

After the subsidies ended, most had contracted to become computer training centers, lacking even a basic telephone connection.

Lessons ignored

The original design of the USD 88 million e Sri Lanka Initiative was based on the lessons of South Africa and elsewhere. Deviating from that design, the present government has placed telecenters branded as Nanasalas located in non-profit settings at the center of e Sri Lanka.

A recent directive ended the original policy of transparently selecting village entrepreneurs to run profit-oriented telecenters as part of the overall mix that included non-profit telecenters as well as the extension of telecom networks for use by end-users as well as resellers.

The original e Sri Lanka design relied on the lessons of previous efforts to extend services to those hitherto excluded from access to telecom networks. Those findings have not changed and Sri Lanka may contribute its own lessons by the time of the ending of external support for telecenters in 2008-09.

This column seeks to contribute to the debate on the wisdom of placing non-profit telecenters at the center of ICT policy, by drawing from the findings of a five-country teleuse at the Bottom of the Pyramid (BOP) study that included the elicitation of responses from around 9,000 teleusers between the ages of 18 and 60 in Socio Economic Classifications D and E (SEC D&E).

What do the people want?

The survey focused on people at the Bottom of the Pyramid (BOP), a term coined by C.K. Prahalad. In the case of Sri Lanka, the survey represents the teleuse of around four million people, with a margin of error of 3 per cent. Questions were asked about all aspects of teleuse, including, of course, the Internet.

At the BOP, just 1.5 percent of Sri Lankans had used the Internet, slightly higher than in India but lower than in Pakistan. Two-point-two per cent of the men at the BOP had used the Internet (less than the 2.9 per cent in Pakistan), more than double the percentage of women who had (0.9 per cent; almost the same as in Pakistan, 0.8 percent).

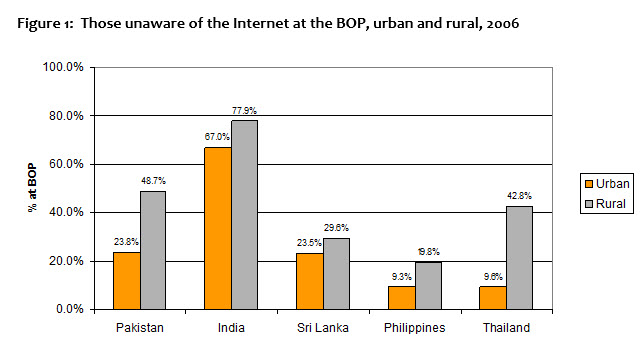

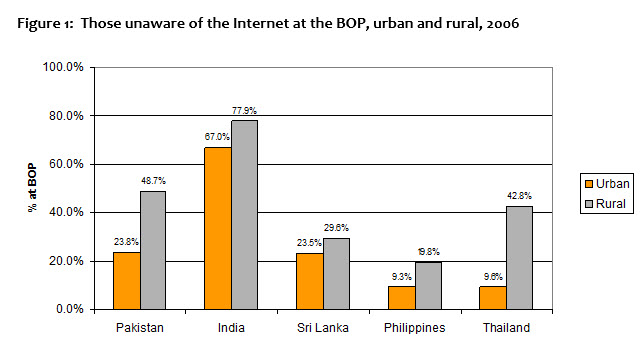

Even if use is terribly low, perhaps awareness is high, promising strong demand. But even that hope is dashed by the data.

Here, we are in better shape than our neighbors, but it still means that three out of 10 people at the BOP claim not to have heard of the Internet. There is more work to be done.

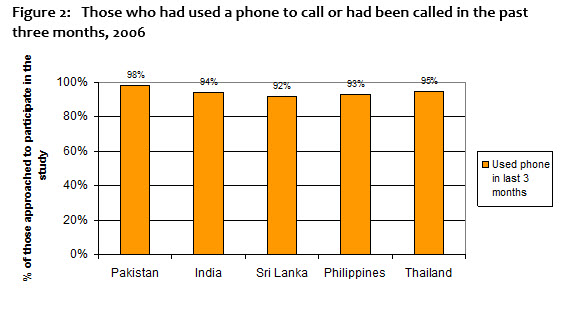

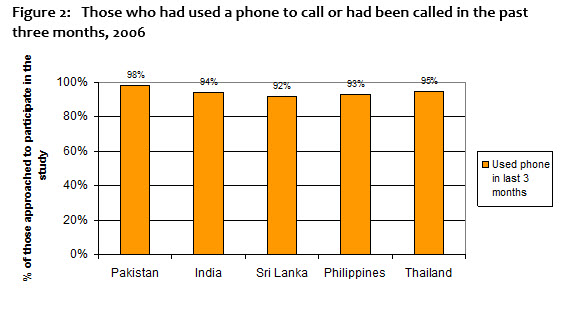

The Internet fares poorly in the survey, but the phone is the star. Almost everyone had used it at least once in the three months prior to the survey:

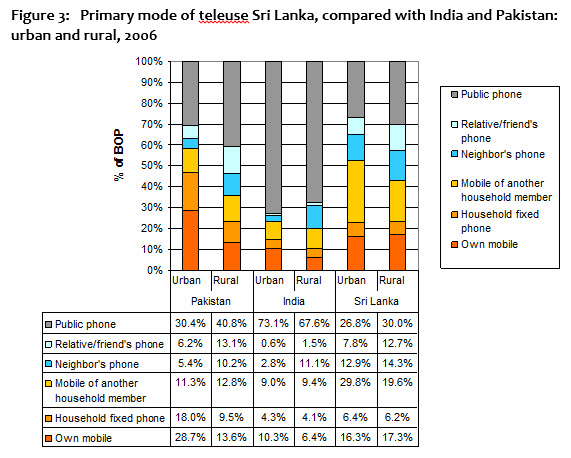

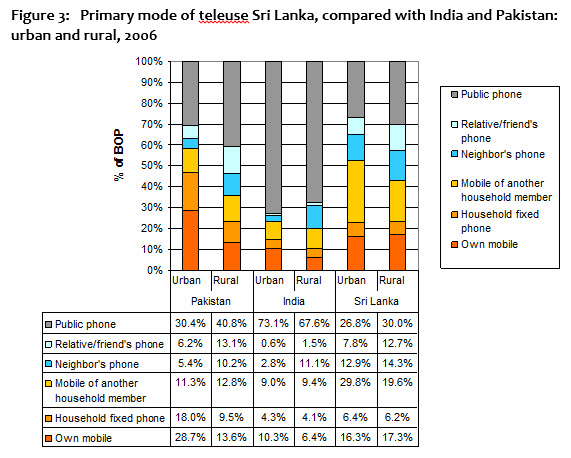

However, a majority of these people had used someone else’s phone to call or be called. They were non-owning users, usually neglected in surveys and policy formulation.

So it was not that these people did not want to use ICTs; they went to great trouble to use the phone; six percent incurred significant additional expense getting to a phone, ranging up to 50 US cents (LKR 50).

This may suggest a business case for telecenters, except for the fact that the satellite provider who supplies telecom services to the Nanasalas cannot do normal calls to local numbers; they can only allow Skype-type calls to those equipped to receive such calls (i.e. those with similar access to a broadband-equipped person computer that is on when the call is made).

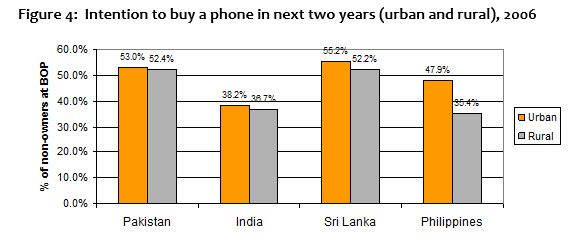

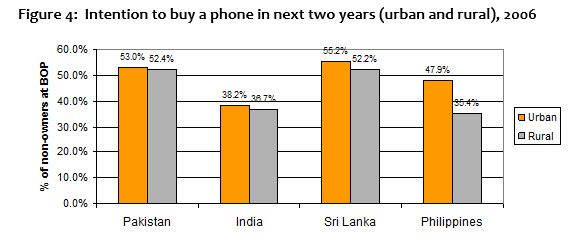

A majority of those who did not have phones now wanted to get them:

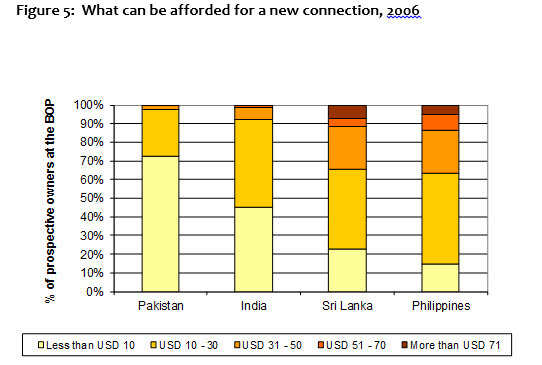

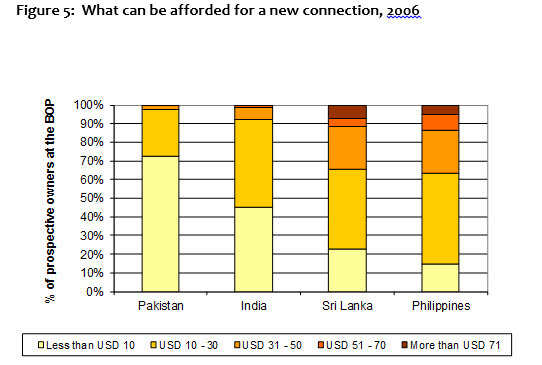

However, they are financially constrained, stating that affordability was the main reason for not having a phone.

Obviously, the CDMA connections being sold for around USD 200 by Sri Lanka Telecom are out of their reach; even the discounted CDMA connections sold by Lanka Bell and Suntel at around USD 60-70 are affordable only to less than 10 per cent of this group. The low-cost handsets and connections being sold by the mobile companies at around USD 40 are affordable to around one third of the BOP.

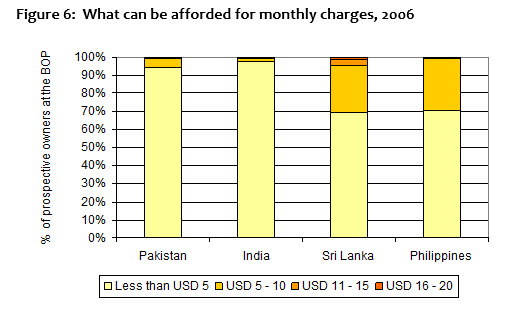

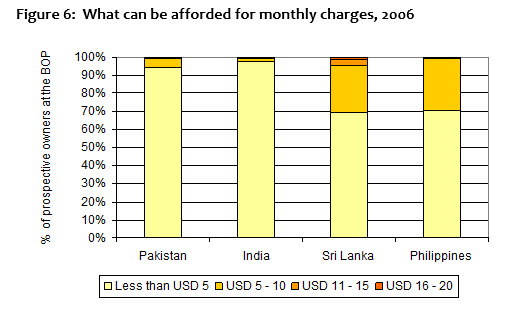

The monthly charges, on the other hand, are affordable. With a little bit of tweaking (low-cost handsets pushing down second-hand prices; installment plans; etc.) it will be possible to connect a new customer for around USD 10-15. The phone is easy to use; most people at the BOP have used one.

New functionalities are being added to the phones, especially mobiles, everyday. It is not just a phone, but a multi-function transactional device. For example, in the Philippines, mobile phones are used to transfer funds within the country and internationally. In Sri Lanka, it’s used for voting (Sirasa Super Star) and to get exam results

The phone is likely to be the technology by which those at the bottom of the pyramid join the Information Society. Even if they want the Internet, is it possible to give them Internet at a price they can afford?

Internet

Telecenters are about the Internet. If they are connected by operators with interconnection agreements with the big seven (SLTL, Dialog, Mobitel, Tigo, Lanka Bell, Suntel and Hutch), it is conceivable for them to offer phone calls, most of which will be local and national calls. But that is not the present arrangement.

In the long run, users must pay for the services they consume. Is it possible to think that regular Internet use will be feasible on around USD 5 (LKR 500) a month? But it is already established that the suppliers of mobile telephony can make profits on that level of monthly spending. The Average Revenues per Subscriber (usually described as ARPU) in South Asia are below USD 7 per month though the operators are making good profits.

Internet in every home at this level of spending is a pipe dream.

Realistic futures

In 2003, when the last Consumer Finance Survey of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka was conducted, slightly over 25 per cent of all households (in all districts other than Mannar, Mulativu and Kilinochchi) had some kind of telephone, fixed or mobile.

By mid 2006, when the LIRNE

asia survey was conducted, 41 per cent of households at the BOP in provinces other than the North and East had either a fixed or a mobile telephone. From this, it could be concluded that the actual household penetration (inclusive of SEC A, B, and C) would be higher.

Fifty three per cent of those currently not owning telephones at the BOP indicated that they planned to obtain a phone within the next two years and are likely to do so, subject of course to their ability to overcome the cost barrier of obtaining the connection.

Therefore it is reasonable to extrapolate that close to 70 per cent of Sri Lankan households would have some kind of telephone by 2009, but even more if the costs of obtaining a connection are brought down from present levels to around USD 10-15.

Even though 91 per cent of those at the BOP could reach a phone within 15 minutes (66 per cent within 5 minutes), most of them were not satisfied with common access and wanted their own phones. Sixty six per cent of current mobile owners at the BOP had made the decision to own the phone because of the convenience of being able to call or be called at any time; nine per cent because they did not want to depend on others; and 20 per cent in Sri Lanka (the largest percentage among the five countries) valued the privacy afforded by a mobile.

Assuming that potential buyers are not fundamentally different from their phone-owning counterparts at the BOP, one may conclude that common access will always be a second-best option at the BOP (as it would be for the readers of this column and the people in charge of ICT policy in government)

If this is the case and the costs of GSM and CDMA connections are rapidly dropping, we will have to assume that most households in Sri Lanka will be connected via narrow-band telephones by 2009 and that their limited communication rupees will be mopped up by mobile/fixed operators. This will further worsen the business case for telecenters.

The inherent limitations of mobile handsets and connections will leave room for common-use facilities for information retrieval (e.g., downloading of forms) and publication. Indeed, the constrained information services made available via mobiles may whet the appetite for full-fledged Internet use.

The teleuse@BOP findings do not suggest that common-use telecenters are doomed to failure in all cases. But they do suggest a serious reexamination of the strategy of placing all World Bank funded eggs in the telecenter basket.

Connecting the young

How shall we connect the Sri Lanka’s young to the Information Society? Improving the policies governing the telecom sector and encouraging the telecom operators to reach out to the willing prospects at the BOP? Or, spending public resources obtained from the World Bank on vanity projects like the Nanasalas that will cease to be viable as soon as the subsidy tap is turned off?

Here, we are in better shape than our neighbors, but it still means that three out of 10 people at the BOP claim not to have heard of the Internet. There is more work to be done.

The Internet fares poorly in the survey, but the phone is the star. Almost everyone had used it at least once in the three months prior to the survey:

Here, we are in better shape than our neighbors, but it still means that three out of 10 people at the BOP claim not to have heard of the Internet. There is more work to be done.

The Internet fares poorly in the survey, but the phone is the star. Almost everyone had used it at least once in the three months prior to the survey:

However, a majority of these people had used someone else’s phone to call or be called. They were non-owning users, usually neglected in surveys and policy formulation.

However, a majority of these people had used someone else’s phone to call or be called. They were non-owning users, usually neglected in surveys and policy formulation.

So it was not that these people did not want to use ICTs; they went to great trouble to use the phone; six percent incurred significant additional expense getting to a phone, ranging up to 50 US cents (LKR 50).

This may suggest a business case for telecenters, except for the fact that the satellite provider who supplies telecom services to the Nanasalas cannot do normal calls to local numbers; they can only allow Skype-type calls to those equipped to receive such calls (i.e. those with similar access to a broadband-equipped person computer that is on when the call is made).

A majority of those who did not have phones now wanted to get them:

So it was not that these people did not want to use ICTs; they went to great trouble to use the phone; six percent incurred significant additional expense getting to a phone, ranging up to 50 US cents (LKR 50).

This may suggest a business case for telecenters, except for the fact that the satellite provider who supplies telecom services to the Nanasalas cannot do normal calls to local numbers; they can only allow Skype-type calls to those equipped to receive such calls (i.e. those with similar access to a broadband-equipped person computer that is on when the call is made).

A majority of those who did not have phones now wanted to get them:

However, they are financially constrained, stating that affordability was the main reason for not having a phone.

However, they are financially constrained, stating that affordability was the main reason for not having a phone.

Obviously, the CDMA connections being sold for around USD 200 by Sri Lanka Telecom are out of their reach; even the discounted CDMA connections sold by Lanka Bell and Suntel at around USD 60-70 are affordable only to less than 10 per cent of this group. The low-cost handsets and connections being sold by the mobile companies at around USD 40 are affordable to around one third of the BOP.

Obviously, the CDMA connections being sold for around USD 200 by Sri Lanka Telecom are out of their reach; even the discounted CDMA connections sold by Lanka Bell and Suntel at around USD 60-70 are affordable only to less than 10 per cent of this group. The low-cost handsets and connections being sold by the mobile companies at around USD 40 are affordable to around one third of the BOP.

The monthly charges, on the other hand, are affordable. With a little bit of tweaking (low-cost handsets pushing down second-hand prices; installment plans; etc.) it will be possible to connect a new customer for around USD 10-15. The phone is easy to use; most people at the BOP have used one.

New functionalities are being added to the phones, especially mobiles, everyday. It is not just a phone, but a multi-function transactional device. For example, in the Philippines, mobile phones are used to transfer funds within the country and internationally. In Sri Lanka, it’s used for voting (Sirasa Super Star) and to get exam results

The phone is likely to be the technology by which those at the bottom of the pyramid join the Information Society. Even if they want the Internet, is it possible to give them Internet at a price they can afford?

Internet

Telecenters are about the Internet. If they are connected by operators with interconnection agreements with the big seven (SLTL, Dialog, Mobitel, Tigo, Lanka Bell, Suntel and Hutch), it is conceivable for them to offer phone calls, most of which will be local and national calls. But that is not the present arrangement.

In the long run, users must pay for the services they consume. Is it possible to think that regular Internet use will be feasible on around USD 5 (LKR 500) a month? But it is already established that the suppliers of mobile telephony can make profits on that level of monthly spending. The Average Revenues per Subscriber (usually described as ARPU) in South Asia are below USD 7 per month though the operators are making good profits.

Internet in every home at this level of spending is a pipe dream.

Realistic futures

In 2003, when the last Consumer Finance Survey of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka was conducted, slightly over 25 per cent of all households (in all districts other than Mannar, Mulativu and Kilinochchi) had some kind of telephone, fixed or mobile.

By mid 2006, when the LIRNEasia survey was conducted, 41 per cent of households at the BOP in provinces other than the North and East had either a fixed or a mobile telephone. From this, it could be concluded that the actual household penetration (inclusive of SEC A, B, and C) would be higher.

Fifty three per cent of those currently not owning telephones at the BOP indicated that they planned to obtain a phone within the next two years and are likely to do so, subject of course to their ability to overcome the cost barrier of obtaining the connection.

Therefore it is reasonable to extrapolate that close to 70 per cent of Sri Lankan households would have some kind of telephone by 2009, but even more if the costs of obtaining a connection are brought down from present levels to around USD 10-15.

Even though 91 per cent of those at the BOP could reach a phone within 15 minutes (66 per cent within 5 minutes), most of them were not satisfied with common access and wanted their own phones. Sixty six per cent of current mobile owners at the BOP had made the decision to own the phone because of the convenience of being able to call or be called at any time; nine per cent because they did not want to depend on others; and 20 per cent in Sri Lanka (the largest percentage among the five countries) valued the privacy afforded by a mobile.

Assuming that potential buyers are not fundamentally different from their phone-owning counterparts at the BOP, one may conclude that common access will always be a second-best option at the BOP (as it would be for the readers of this column and the people in charge of ICT policy in government)

If this is the case and the costs of GSM and CDMA connections are rapidly dropping, we will have to assume that most households in Sri Lanka will be connected via narrow-band telephones by 2009 and that their limited communication rupees will be mopped up by mobile/fixed operators. This will further worsen the business case for telecenters.

The inherent limitations of mobile handsets and connections will leave room for common-use facilities for information retrieval (e.g., downloading of forms) and publication. Indeed, the constrained information services made available via mobiles may whet the appetite for full-fledged Internet use.

The teleuse@BOP findings do not suggest that common-use telecenters are doomed to failure in all cases. But they do suggest a serious reexamination of the strategy of placing all World Bank funded eggs in the telecenter basket.

Connecting the young

How shall we connect the Sri Lanka’s young to the Information Society? Improving the policies governing the telecom sector and encouraging the telecom operators to reach out to the willing prospects at the BOP? Or, spending public resources obtained from the World Bank on vanity projects like the Nanasalas that will cease to be viable as soon as the subsidy tap is turned off?

The monthly charges, on the other hand, are affordable. With a little bit of tweaking (low-cost handsets pushing down second-hand prices; installment plans; etc.) it will be possible to connect a new customer for around USD 10-15. The phone is easy to use; most people at the BOP have used one.

New functionalities are being added to the phones, especially mobiles, everyday. It is not just a phone, but a multi-function transactional device. For example, in the Philippines, mobile phones are used to transfer funds within the country and internationally. In Sri Lanka, it’s used for voting (Sirasa Super Star) and to get exam results

The phone is likely to be the technology by which those at the bottom of the pyramid join the Information Society. Even if they want the Internet, is it possible to give them Internet at a price they can afford?

Internet

Telecenters are about the Internet. If they are connected by operators with interconnection agreements with the big seven (SLTL, Dialog, Mobitel, Tigo, Lanka Bell, Suntel and Hutch), it is conceivable for them to offer phone calls, most of which will be local and national calls. But that is not the present arrangement.

In the long run, users must pay for the services they consume. Is it possible to think that regular Internet use will be feasible on around USD 5 (LKR 500) a month? But it is already established that the suppliers of mobile telephony can make profits on that level of monthly spending. The Average Revenues per Subscriber (usually described as ARPU) in South Asia are below USD 7 per month though the operators are making good profits.

Internet in every home at this level of spending is a pipe dream.

Realistic futures

In 2003, when the last Consumer Finance Survey of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka was conducted, slightly over 25 per cent of all households (in all districts other than Mannar, Mulativu and Kilinochchi) had some kind of telephone, fixed or mobile.

By mid 2006, when the LIRNEasia survey was conducted, 41 per cent of households at the BOP in provinces other than the North and East had either a fixed or a mobile telephone. From this, it could be concluded that the actual household penetration (inclusive of SEC A, B, and C) would be higher.

Fifty three per cent of those currently not owning telephones at the BOP indicated that they planned to obtain a phone within the next two years and are likely to do so, subject of course to their ability to overcome the cost barrier of obtaining the connection.

Therefore it is reasonable to extrapolate that close to 70 per cent of Sri Lankan households would have some kind of telephone by 2009, but even more if the costs of obtaining a connection are brought down from present levels to around USD 10-15.

Even though 91 per cent of those at the BOP could reach a phone within 15 minutes (66 per cent within 5 minutes), most of them were not satisfied with common access and wanted their own phones. Sixty six per cent of current mobile owners at the BOP had made the decision to own the phone because of the convenience of being able to call or be called at any time; nine per cent because they did not want to depend on others; and 20 per cent in Sri Lanka (the largest percentage among the five countries) valued the privacy afforded by a mobile.

Assuming that potential buyers are not fundamentally different from their phone-owning counterparts at the BOP, one may conclude that common access will always be a second-best option at the BOP (as it would be for the readers of this column and the people in charge of ICT policy in government)

If this is the case and the costs of GSM and CDMA connections are rapidly dropping, we will have to assume that most households in Sri Lanka will be connected via narrow-band telephones by 2009 and that their limited communication rupees will be mopped up by mobile/fixed operators. This will further worsen the business case for telecenters.

The inherent limitations of mobile handsets and connections will leave room for common-use facilities for information retrieval (e.g., downloading of forms) and publication. Indeed, the constrained information services made available via mobiles may whet the appetite for full-fledged Internet use.

The teleuse@BOP findings do not suggest that common-use telecenters are doomed to failure in all cases. But they do suggest a serious reexamination of the strategy of placing all World Bank funded eggs in the telecenter basket.

Connecting the young

How shall we connect the Sri Lanka’s young to the Information Society? Improving the policies governing the telecom sector and encouraging the telecom operators to reach out to the willing prospects at the BOP? Or, spending public resources obtained from the World Bank on vanity projects like the Nanasalas that will cease to be viable as soon as the subsidy tap is turned off?